Is Compass really a tech company?

/Earlier this month, The Real Deal published an excellent article about Compass. And the article included one of my favorite things: numbers.

Why it matters: Opinions aside, the latest numbers allow us to compare Compass to its peers, and really answer dual questions: Is Compass doing anything novel in the industry, and is it really a technology company?

Comparing growth rates

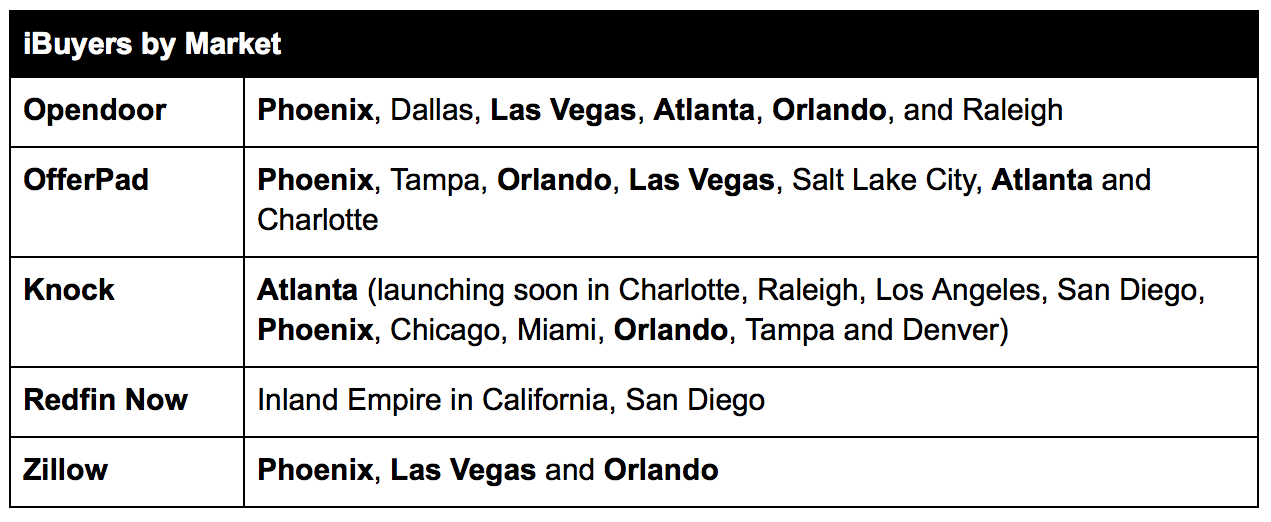

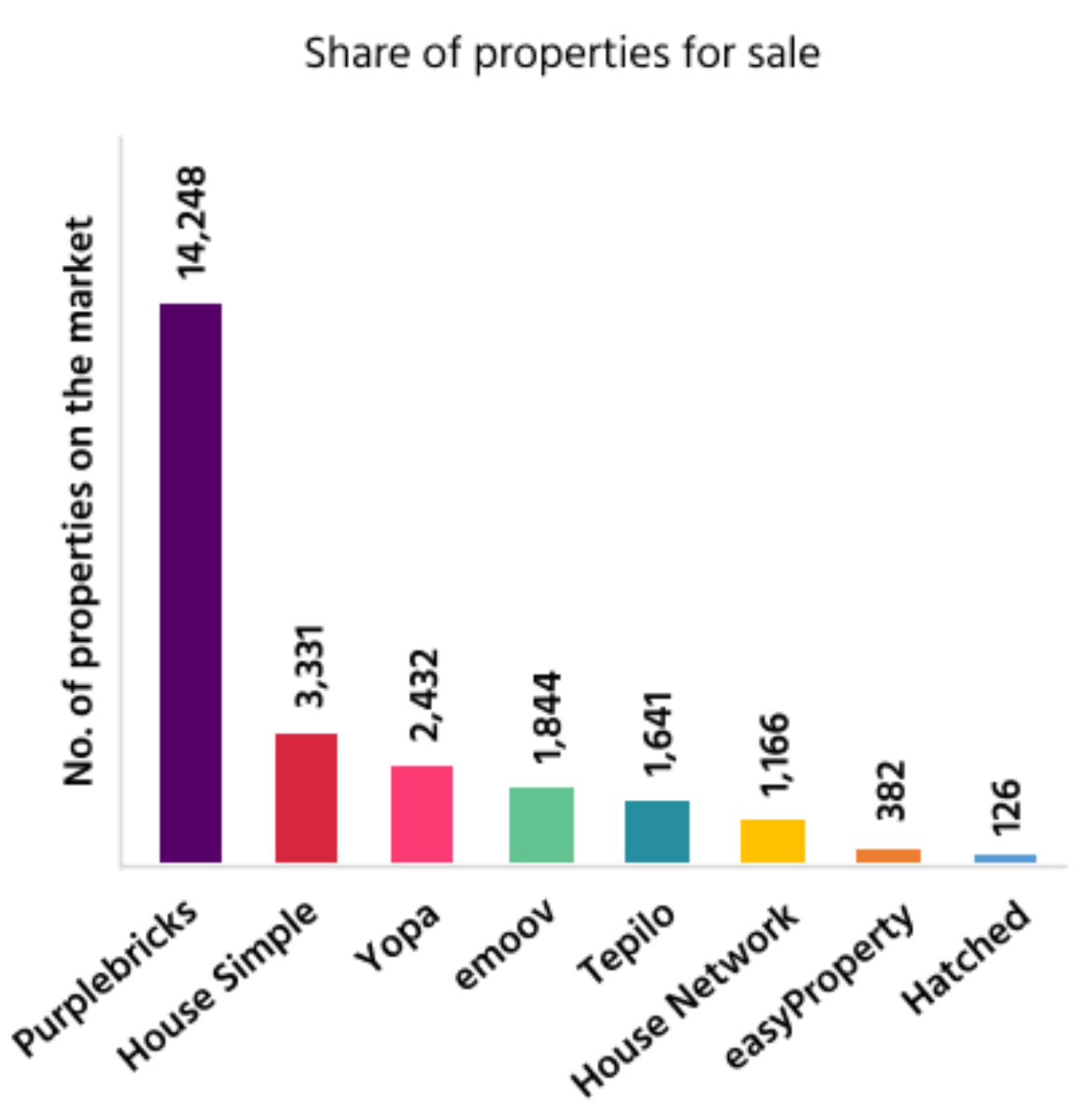

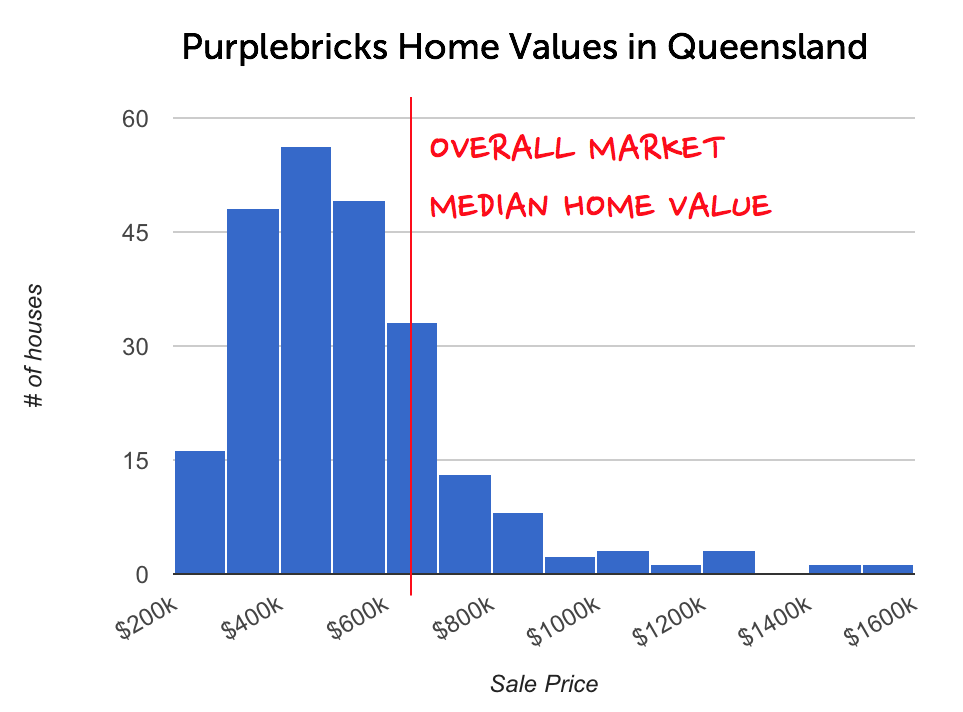

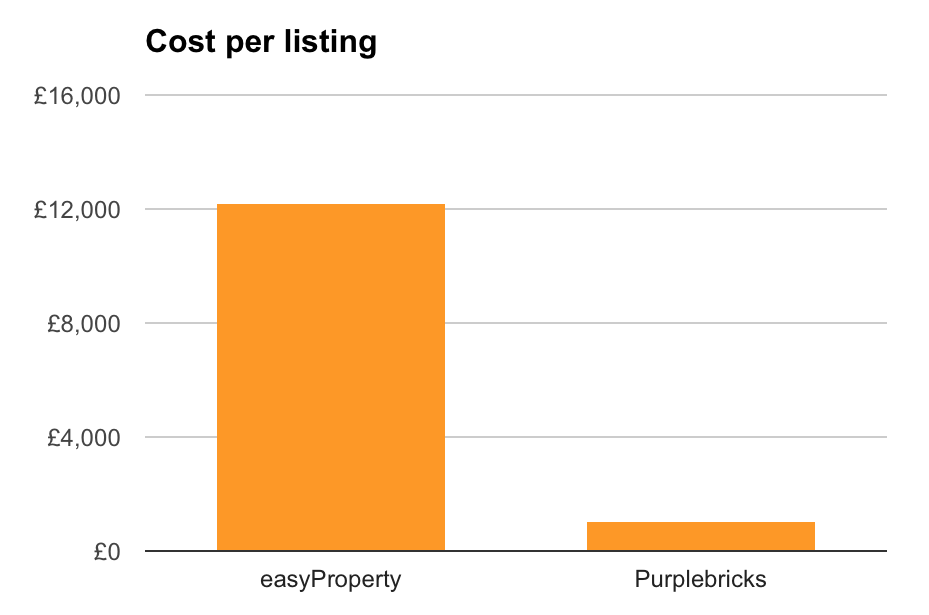

I'll be comparing Compass to two of its peers: Redfin and Purplebricks. Both businesses, which I know well, represent the most successful new models in real estate that are changing the way people buy and sell houses. They are successful in terms of overall revenue and transaction volumes, demonstrating market traction at scale.

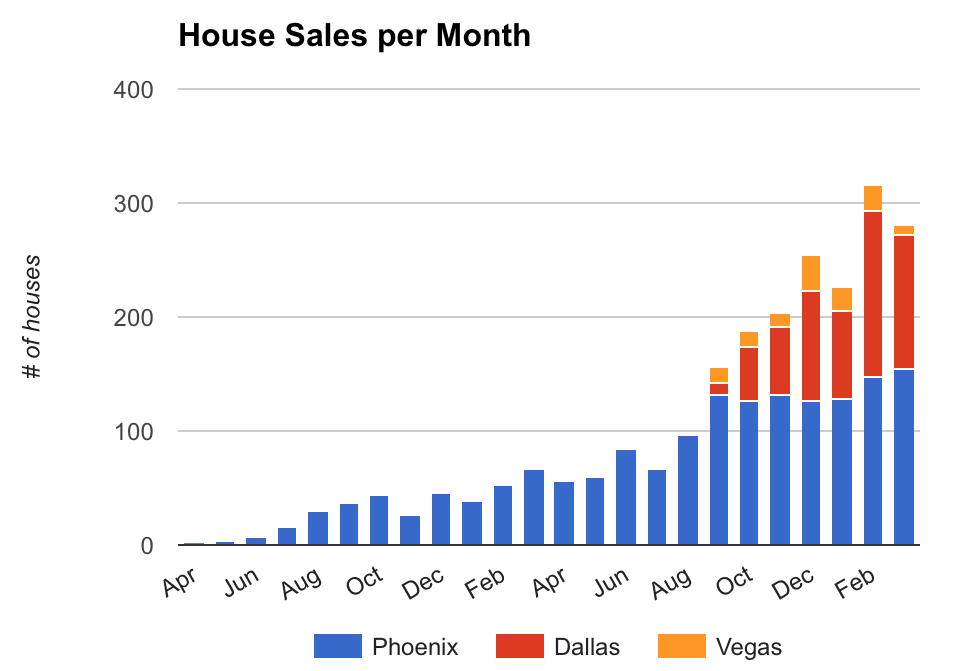

Overall revenue growth for all three firms is growing impressively. It's undeniable that Compass' revenue growth is accelerating.

The core of the Compass business model is making acquisitions. Armed with $800 million in venture capital, it is aggressively buying up agents and brokerages.

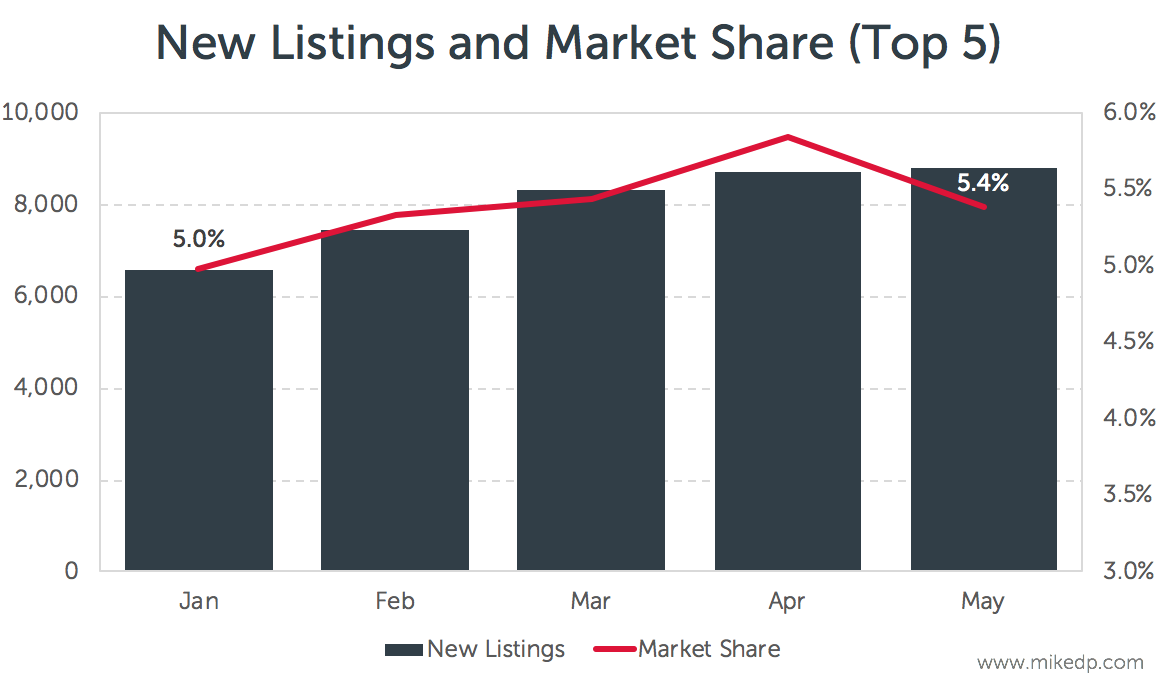

Transaction volumes are all increasing. Again, Compass' projected growth in 2018 is impressive, but that's what happens when you buy market share. By comparison, Redfin and Purplebricks are growing organically.

Is the Compass model novel?

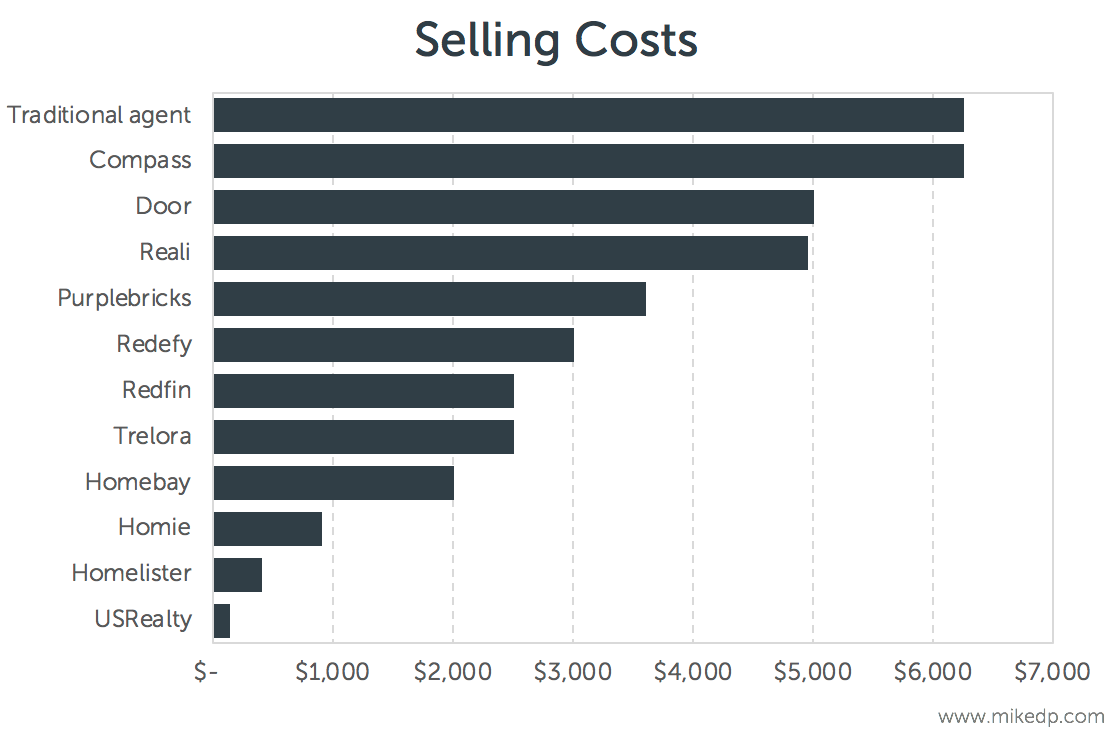

The Compass investment thesis centers around technology. It claims that it is a tech company (with tech company valuations), and is building the "first modern real estate platform" that provides "real estate agents tools that increase efficiency."

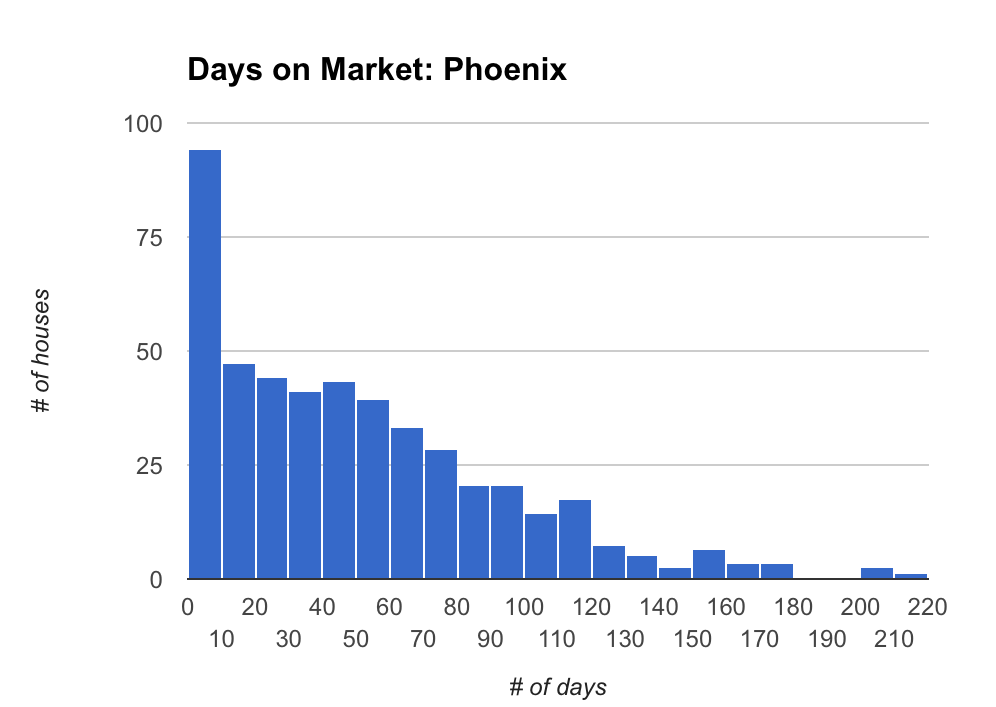

The data has yet to prove out this thesis. Starting with another tech company, Redfin, the numbers show that it is clearly a more efficient business than Compass -- because its operating model is different.

For Compass 2018, I've included two numbers: 7,480 is the total current number of employees, while 4,800 is the midpoint between 2017 and 2018. Given that Compass is growing so quickly, it makes sense to look at both to calibrate the comparison.

The data above is total number of employees. If we look at overall agent efficiency, as I did earlier this year when comparing Compass, Redfin, and Purplebricks in the U.K., the contrast is more pronounced.

The evidence shows that, at best, Compass agents may be incrementally more efficient than the industry average, but Redfin and Purplebricks agents are exponentially more efficient.

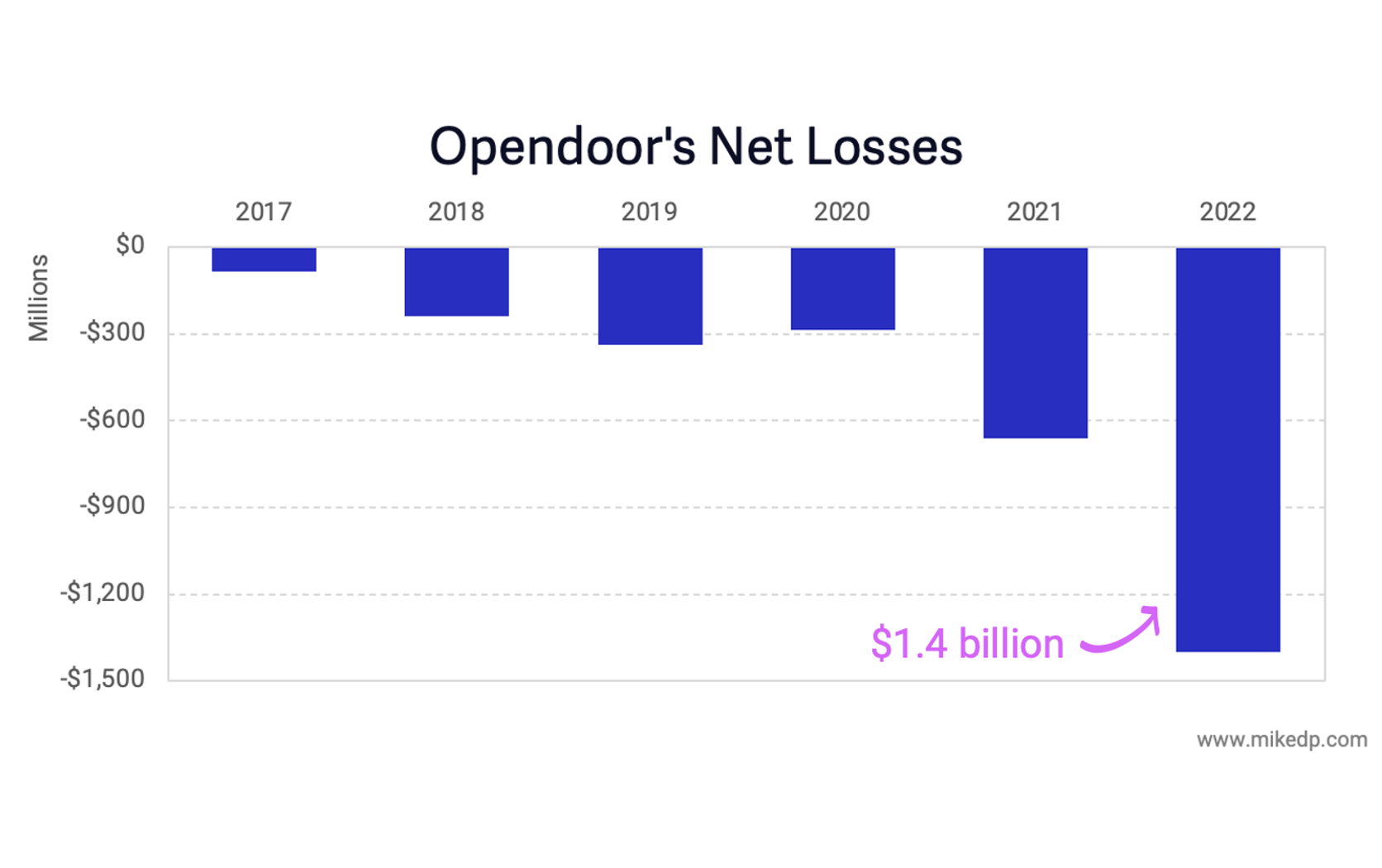

Compass' growth strategy is novel: raise a massive amount of capital and use it to acquire market share. But the operational model of the business is fundamentally the same as every other traditional brokerage -- as the data around efficiency shows. It's not really changing the industry in the same way that Redfin, Purplebricks, or Opendoor are -- it's just moving market share around.

Is Compass a technology company?

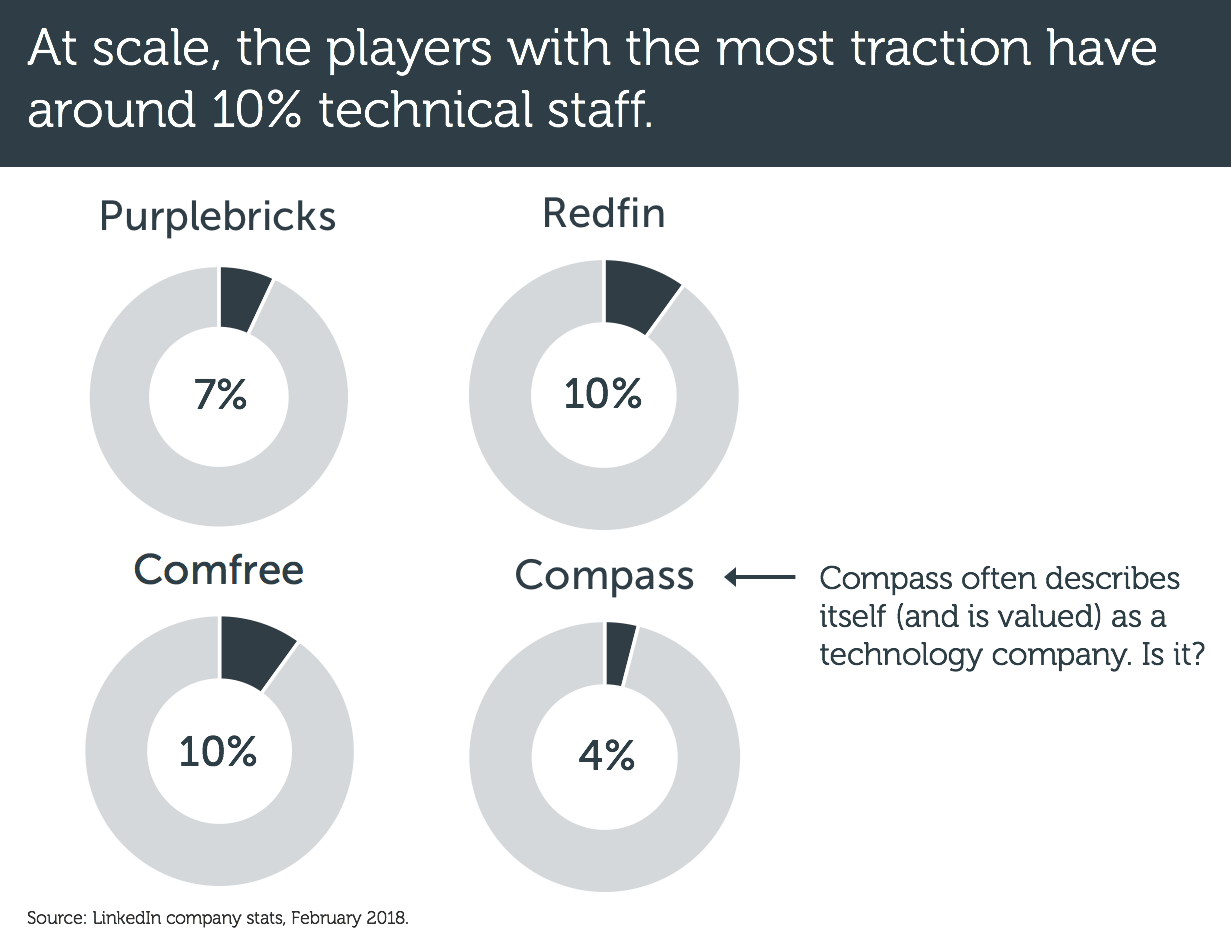

Analysis I conducted in early 2018, as part of my Emerging Models in Real Estate Report, showed that -- roughly speaking -- about 10 percent of the staff of global leaders was technical. Compass was the outlier at 4 percent.

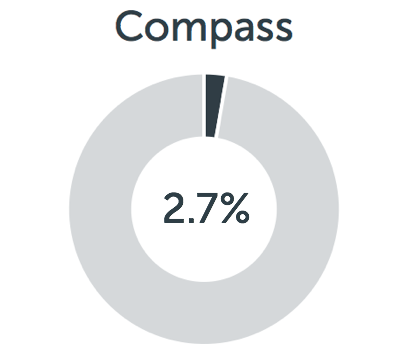

Using the latest data (7,480 total employees and a 200-person tech team), that percentage has dropped to 2.7 percent.

Even if you calibrate for Compass' fast agent employee growth through acquisition, the overall percentage is still considerably lower than its peers.

Strategic considerations

There are a few final points to consider when looking at Compass:

Being a tech company is not a binary thing, but what is clear is that Compass is less of a tech company than its peers.

As opposed to Purplebricks and Redfin, Compass' customer is the agent. The technology it is building is for agents, not consumers.

True, exponential efficiency gains come with technology combined with a novel operating model. Technology alone won't deliver it.