Traditional vs Tech: How the U.K.’s biggest real estate incumbent is reacting to digital disruption

/Written in collaboration with Eddie Holmes, partner at PropTech Consult.

It’s indisputable that digital transformation is occurring in real estate and changing the way people buy and sell houses. Nowhere around the world is this more evident than in the U.K., where upstart online agencies like Purplebricks have captured market share and are growing fast.

Often, we spend most of our time looking at the disruptors. But for every disrupter, there are those being disrupted. In this case that’s Countrywide, the U.K.’s largest estate agency group.

Countrywide’s stock price is down over 50 percent during the past 12 months, shedding hundreds of millions of pounds in value.

But the firm hasn’t stayed still; in 2016 it launched its own online offering, which is now rolling out across its massive network. But while credit should be given for moving early and quickly, Countrywide’s strategy raises serious questions around the viability of the offering and if it was, in fact, designed to fail.

Background

Countrywide is the largest estate agency group in the U.K. Founded in 1986 following the acquisition of two estate agencies by Hambros, the company grew through sustained acquisitions of businesses such as Nationwide and John D Wood estate agents.

Today it employs 11,300 personnel across 1,500 branches under 47 high street brands.

Trading as a property services business, rather than simply an estate agency, Countrywide provides a range of services to homebuyers, sellers, renters and landlords.

Countrywide has been the hardest hit estate agency incumbent in the U.K.

The perfect storm of macro economic factors affecting the housing market combined with the rising competition from online agencies has brought immense pressure on its business.

This has come about in the context of an organization that was not known for the robustness or depth of their technology systems before the market dynamics changed.

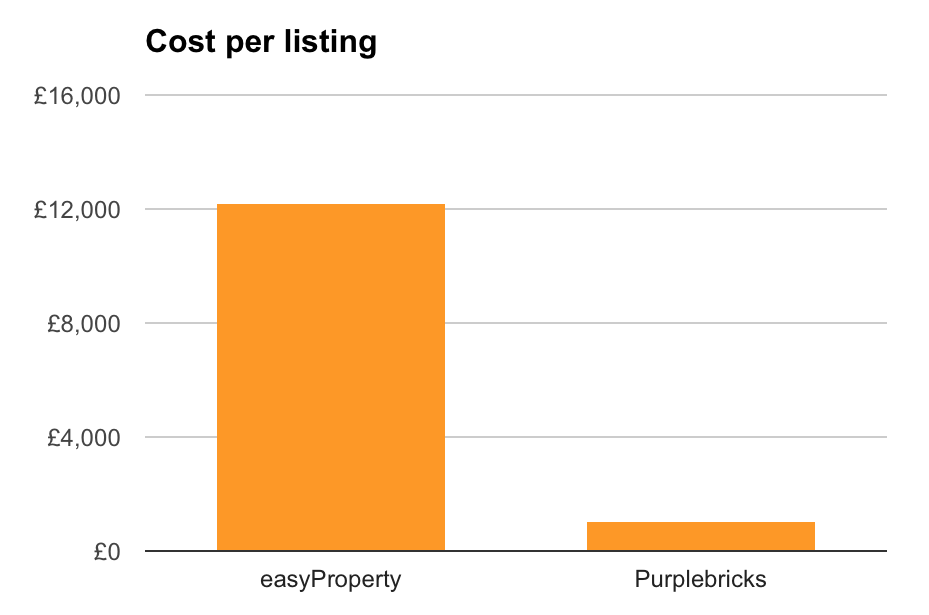

Purplebricks is the largest of a new breed of online agencies. Its proposition to homeowners is a low, fixed-fee, combined with smart technology to save consumers thousands of pounds when selling their home.

Together, these firms have captured 6 percent of the market in the U.K., and continue to grow.

To illustrate their different fortunes and trajectories, the chart below shows share price changes over the past 16 months for Countrywide (orange) and Purplebricks (blue):

Countrywide’s stock price has taken a hammering. Meanwhile, Purplebricks’ market cap is greater than the two largest listed estate agency groups in the U.K. combined, showing a clear picture of where the investment community sees the future of the industry.

If the investment community was bearish on the entire real estate market, Purplebricks’ market cap would be much lower. But the reality of the markets shows a clear preference toward where the future lies.

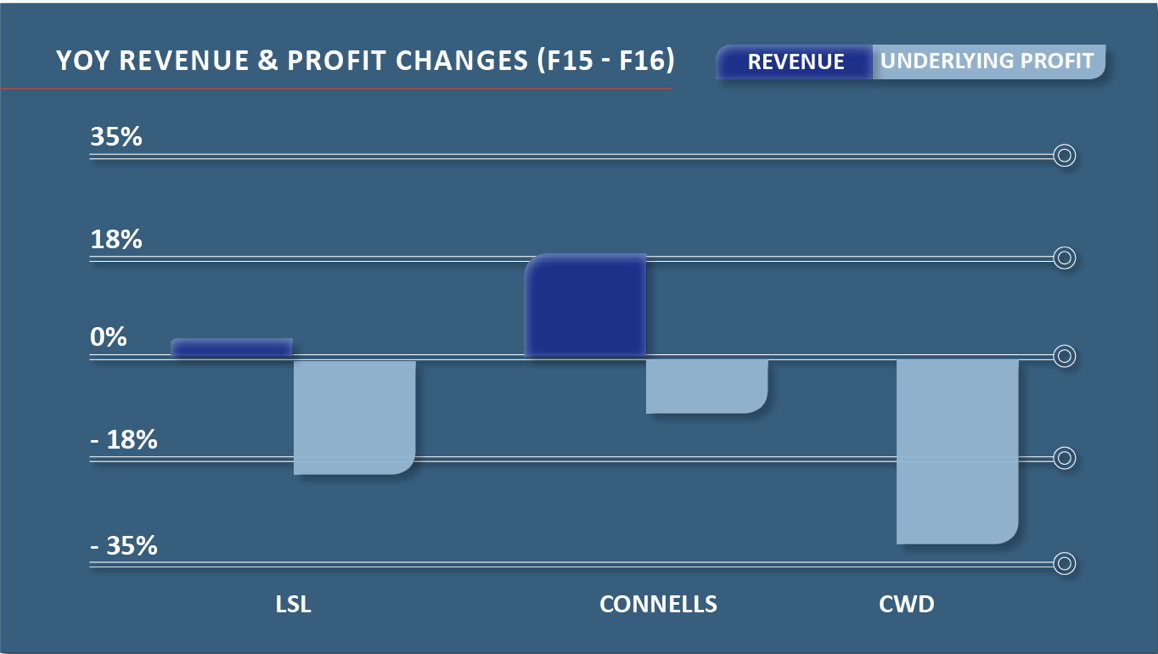

This market pressure is affecting all estate agency groups in the U.K. The chart below shows how three of the largest players have seen their revenues and profits impacted over the past 12 months. Countrywide is not alone, but it has been the hardest hit:

We’re at a pivotal point for the entire industry and for Countrywide in particular. This is a business in decline, and the line between death spiral and a rebirth is razor thin. The chart below shows the Countrywide story as only numbers can do: flat revenues and decimated profits.

Anthony Codling, an analyst at the investment banking group Jefferies — which has previously acted for Countrywide — sums up his position: “Although Countrywide may be down, it is not out and if what doesn’t kill us makes us stronger, we expect the group to emerge strongly from the storm once it has run its course.”

But it is still unknown if this will kill Countrywide. Only time — and its strategy to combat the rising tide of online agencies — will tell.

Countrywide reacts

Countrywide’s strategy became clear in 2015 and has two main pillars under the title “Building Our Future.”

- Launch an online hybrid competitor of its own (the multichannel approach)

- Rationalize the existing business by closing branches and consolidating brands

These efforts resulted in the pilot launch of its new, online offering in May 2016, and the closing of 200 branches and four brands in 2016 (leaving Countrywide with 991 branches and 47 brands).

The restructuring of its business didn’t come cheap; £8.1 million of redundancy costs and £15.8 million of property closure costs, plus a £19.6 million goodwill impairment charge.

The investment in the new technology platform was an outsourced build, rumored to cost an additional £6 million, while salary expenses for the year increased £6 million to £366 million.

Clearly, Countrywide is spending significant cash and investing in both pillars of the strategy. It has also executed both pillars simultaneously, which must have caused significant cultural challenges among the workforce at a time when laser focus on the online pilot — instead of restructuring — was critical.

An inconclusive pilot

Countrywide sensibly rolled out its new online offering across three test markets. This allowed it to get to market fast, collect real customer feedback, and (we assume) incorporate that feedback back into the product.

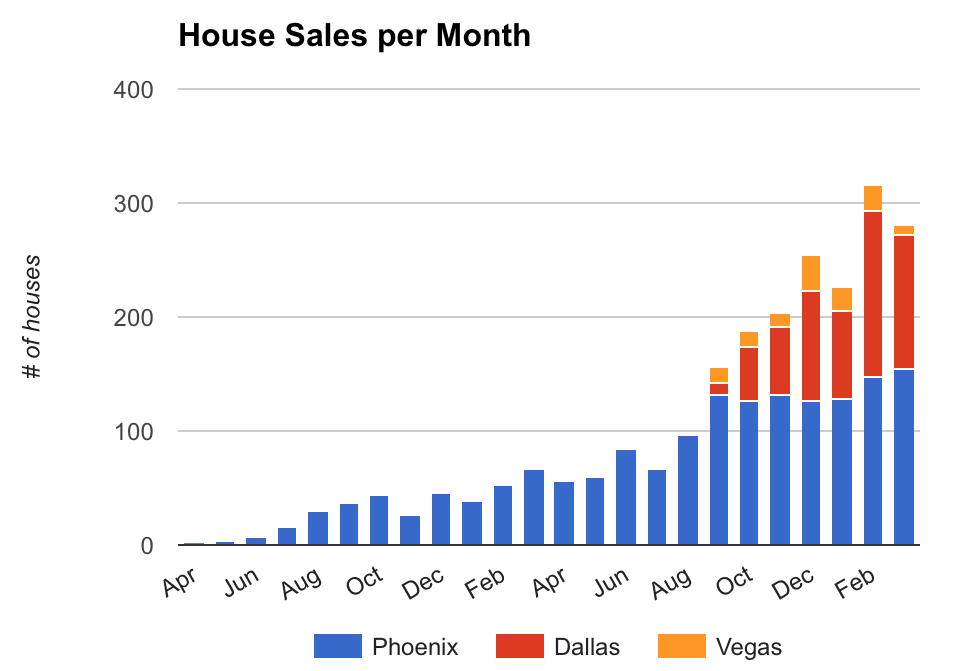

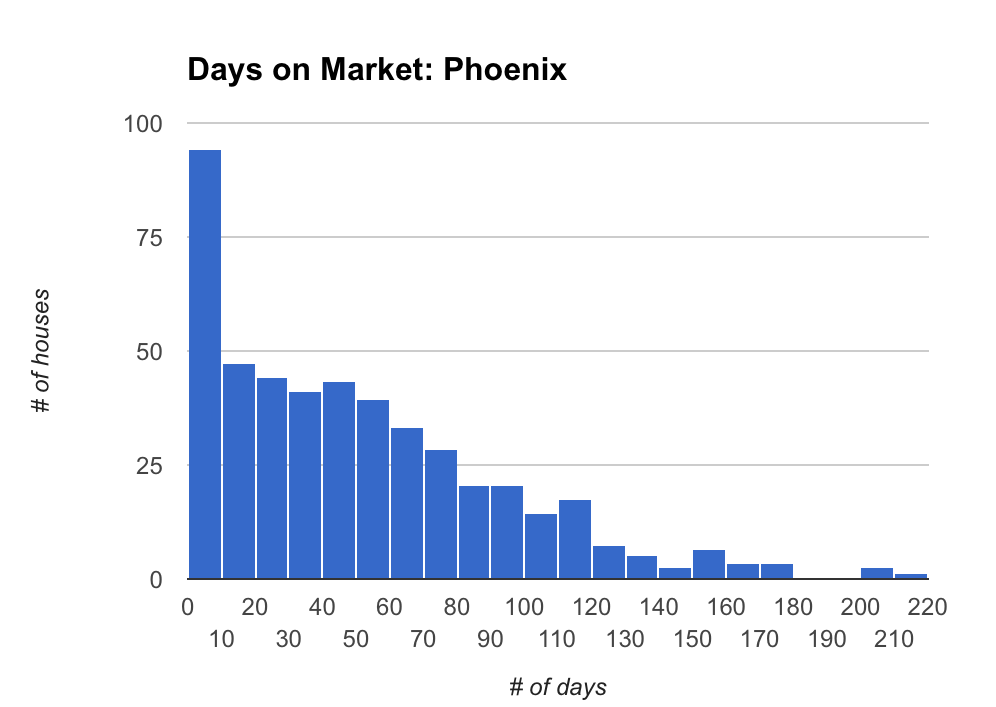

The data below tracks Countrywide’s daily listings via the three brands used to pilot the scheme and shows that overall listings are down versus the previous pre-pilot performance:

Systemic issues with the offering

Countrywide ran its pilot and subsequently launched its online offering under its existing brands and corporate structure. It is positioned as an additional service, rather than as a separate offering, as evidenced from the messaging below.

This means that the new offering — which is being offered at a fraction of the cost of existing services — is operating within the same cost structure, making it difficult to turn a profit.

Marketing this service under the existing Countrywide brands and utilizing existing marketing channels (in the case above, the Entwistle Green website) raises some questions about the purpose of the service.

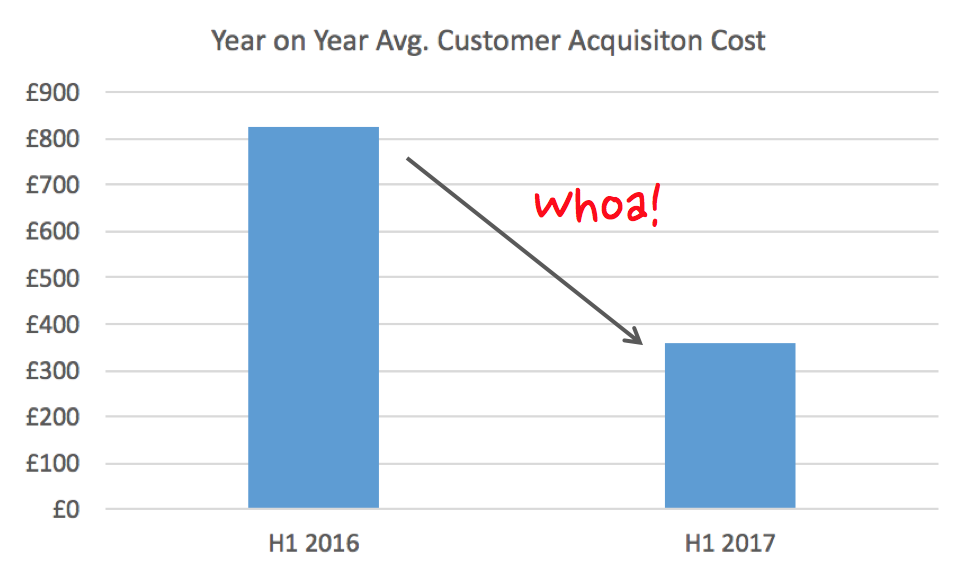

It is widely accepted that tech-driven businesses typically acquire newcustomers in new ways when compared to their traditional business competitors (for example, through smart digital marketing).

The ultimate goal of pushing services through new channels is to achieve an element of virality in the spread of the product, which reduces the cost of customer acquisition and creates the opportunity for larger profit margins.

However, by using traditional marketing channels under existing brands, Countrywide is not likely to reach new customers in new ways.

Instead, it is only reaching those potential customers who already know their existing brands well enough to find themselves on the website. Therefore it only serves to cannibalize the existing customer base by selling them a lower priced service while simultaneously failing to bring in new customers.

The brand extension problem

In March of this year, Australia’s second biggest real estate group, LJ Hooker, announced that it would launch its own DIY real estate disruptor, Settl. The new brand empowers vendors to sell their homes online, in exchange for paying a low fixed fee. It is a direct response to Purplebricks’ 2016 launch into the Australian market.

The key difference between LJ Hooker’s Settl and Countrywide’s online efforts is one of brand. LJ Hooker is creating a new “fighter” brand, while Countrywide is opting for a brand extension.

A fighter brand is designed to combat low-price competitors while protecting an organization’s premium-price offerings.

Imagine you own a lemonade stand that sells premium lemonade. You’ve been in business for years and are well known for offering premium beverages.

One day a low-cost lemonade stand opens across the road, offering lemonade at a tenth your price.

What LJ Hooker has done with Settl is to tackle the new competitor by opening its own, separate low-cost lemonade stand. To the customer’s eye, there is no connection with the existing LJ Hooker brand or the premium values associated with it.

What is Countrywide attempting to do? Sell low-cost lemonade alongside its premium lemonade, at the same stand. Not only is this confusing to customers, but it cannibalizes its existing premium business.

The history of fighter brands is not hugely positive. However, excellent examples can be seen with Intel’s launch of the Celeron processor to combat the threat of low price AMD chips, and the creation of JetStar by Qantas to see off the threat of low cost rival Virgin Blue.

(For more on fighter brands, see “Should You Launch a Fighter Brand?” on Harvard Business Review.)

By launching a brand extension, Countrywide is missing out on the classic benefits of a fighter brand: eliminating competition, protecting the existing premium offering, and opening up new, lower-end markets for the organization. Countrywide’s approach begs the question: Is the offering truly meant to succeed?

Conclusions

The fact that Countrywide’s online offering is a brand extension that does not offer the benefits of a fighter brand leads to two equally straightforward conclusions.

Either the entire endeavor is ill-fated due to major strategic positioning issues, or it is simply a lead-gen effort to support the incumbent business. The continued pursuit, at the cost of a £38m rights issue, of the strategy after an inconclusive pilot suggests this is the case.

Countrywide felt forced to do something; online agencies are perceived by the financial markets to be the greatest threat to its existing business. Purplebricks’ continued momentum, market traction, and rising stock price demanded a response from senior management.

There were a number of options available.

Countrywide could have invested in or acquired another online player in the market, it could have launched its own disruptive brand (as LJ Hooker has done with Settl), or it could have launched a new offering internally.

For whatever reason, the choice is the latter. Viewed from the outside, Countrywide now offers a service on par with the online agencies.

It can tell the market and prospective customers that it also offers a low-fee, online offering. However, customers don’t seem to be buying the new service and the markets aren’t buying the strategy.

In reality, the brand extension offering cannot succeed on its own.

At best, it achieves product parity with online agencies, and offers a platform to upsell potential customers to its premium estate agency proposition.

However, it does not suggest that the business has thoroughly understood the challenges that this must create around issues such as incentivization of staff or servicing a totally new service line with the existing infrastructure and cost base.

If Countrywide’s offering was designed to fail — that is, to not succeed as a standalone business or product, but as lead-gen for its existing business — it does not mean it is a bad strategy.

In fact, it may be the best course of action for the large incumbent as it is relatively low risk and keeps its options open. But if the offering was not designed to fail, significant changes are clearly required to give it a chance of success.