Inside Opendoor: what two years of transactions say about their prospects

/Read every analysis I've posted on Opendoor, Zillow Offers, and the iBuyer business model.

This article was co-written with Sib Mahapatra, former manager of strategy at Redfin, and now an entrepreneur and real estate tech enthusiast based in San Francisco.

Raising $210 million is enough to get any business into the news. That’s especially true when the business in question is Opendoor, the 2-year-old real estate startup that aims to bring simplicity to the housing market by purchasing homes directly from sellers and flipping them over to buyers after a quick spruce-up.

This latest infusion of capital, announced in late November, brings Opendoor’s total war chest to $320 million. Based in San Francisco and led by CEO Eric Wu, Opendoor plans to use the capital to expand its active market presence from Phoenix and Dallas to 10 cities by the end of 2017.

Investors and stakeholders in residential real estate have eyed Opendoor with wary interest since the company was launched as “Project Homerun” in July 2014 by former PayPal exec Keith Rabois. With tons of dry powder and two years of operations in Phoenix behind it, Opendoor is building momentum: the company is already the largest brokerage in Phoenix by transaction volume.

Key questions

Now that Opendoor has a track record and a mandate to grow, it’s a good time to assess its progress to date and provide an informed perspective on the following question: is Opendoor the way forward for residential real estate? Does the Opendoor model represent a sustainable, profitable and scalable platform for reinventing how homes are bought and sold?

Several thought-pieces have explored the pros and cons of Opendoor’s business model and its impact on the real estate industry at a high level. Our goal is to dig deeper by using public records and MLS data to shed light on Opendoor’s transaction history and inform a bottoms-up analysis of the unit economics and viability of the business. By the end of this analysis, we’ll provide answers to three questions that underlie the proposition above:

How much money does Opendoor make per transaction? Is Opendoor offering its customers a fair value for houses?

How big could this model really get in the U.S.?

Does Opendoor have a sustainable competitive advantage against competitors that might enter the space?

Business model

Before jumping into the overall revenue opportunity in the U.S. market, it’s worth understanding Opendoor’s business model and how it makes money. Here are the key takeaways:

Opendoor buys houses and owns them, acting as a middleman (as opposed to a matchmaker) in residential real estate transactions.

Opendoor won’t buy every house -- qualifying properties include single-family homes built after 1960 with a value between $125,000 and $500,000.

Opendoor makes money in two ways: from the service fees it charges, and from any difference between what it buys houses for and what it sells them for.

Opendoor works with real estate agents, offering to pay full buyer commissions, as well as seller commissions if a sale comes from an agent.

Opendoor charges a variable fee for its services, starting at 6 percent and rising to 12 percent for more risky properties. The average fee falls between 8 percent and 9 percent for sellers, which is higher than the standard 6 percent fee charged by traditional real estate agents. But with the higher fees come certainty around a transaction.

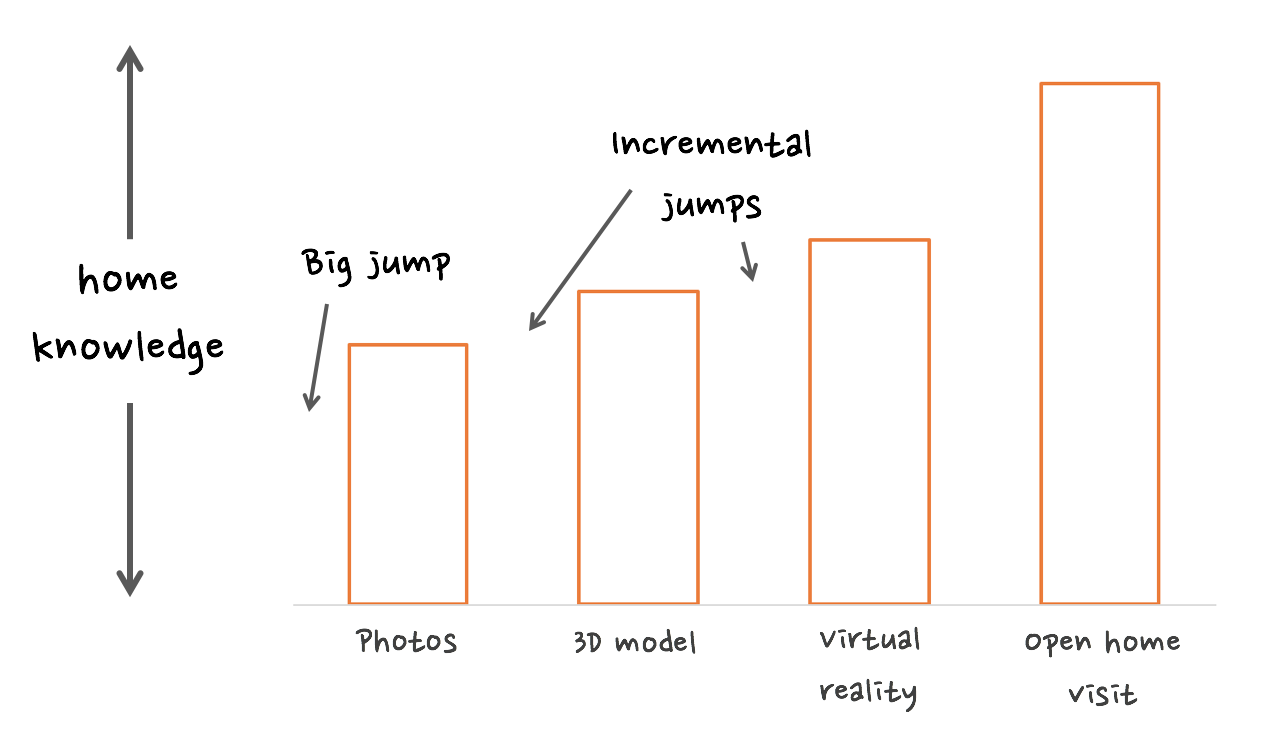

The customer proposition for using Opendoor is strong. For home sellers, Opendoor offers to eliminate all of the hassle and uncertainty of selling a house with a simple, transparent offer. In other words: don’t worry about fixing the fence, mowing the lawn, picking the right agent, and wondering if and when your home will finally sell.

Opendoor takes care of it all, completing the whole process in a matter of days. In our opinion, it’s a seller experience that’s truly 10x better than the status quo.

Opendoor’s unique model lets it offer industry-leading benefits to buyers, too:

All day open homes, seven days a week

30-day satisfaction guarantee (if you don’t like the home, they’ll buy it back)

2-year home warranty

Upside and revenue opportunity

It’s hard to argue against Opendoor’s compelling seller value proposition. But can the business make money and become profitable enough to justify its massive valuation?

First we need to understand how much money Opendoor makes on each transaction. We’re going to stay focused on revenue for the moment and not worry about costs (yet). As discussed above, Opendoor makes money from the service fees it charges, plus any difference between what it buys houses for and what it sells them for.

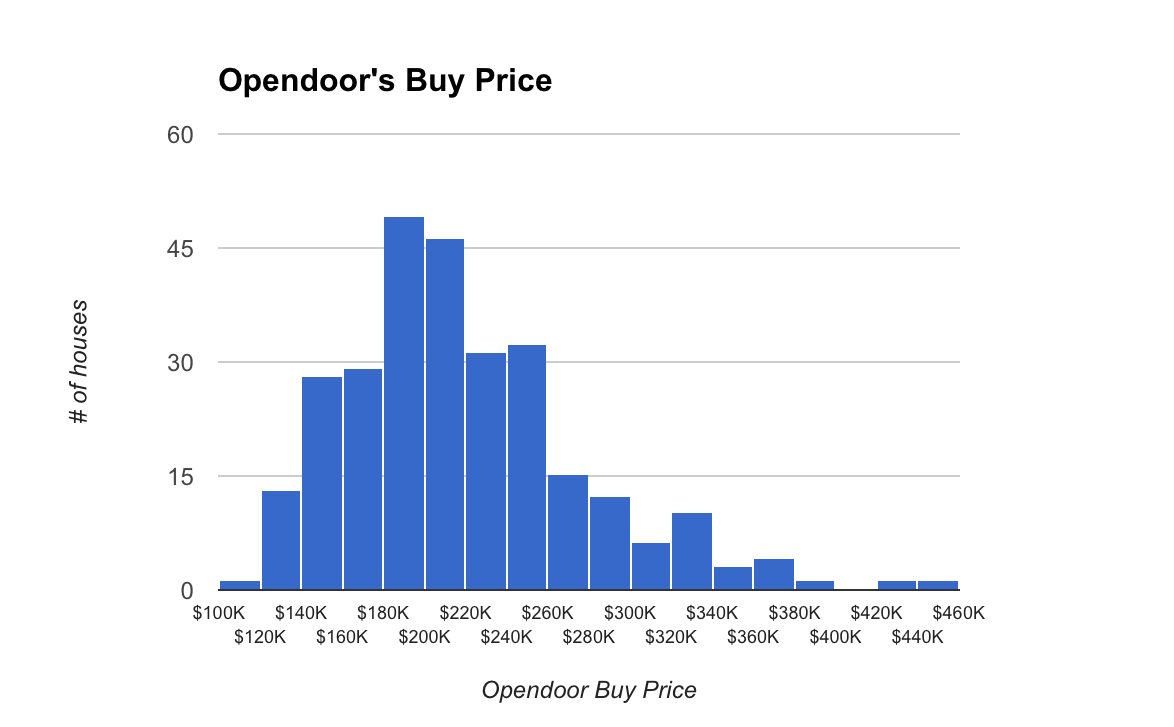

The analysis of average purchase value and appreciation below is based on over 350 recent listings in the Phoenix market where Opendoor bought a home, relisted it on the market, and in the case of 235 listings, eventually sold it. We also looked at over 1,500 Opendoor MLS listings throughout 2016 to get a sense of the firm's traction in Phoenix.

The chart below shows the number of sales per month in the Phoenix market over the past 20 months. As you can see, traction has increased to over 120 sales per month.

The average price paid by Opendoor for a home in Phoenix is $217,370, and is tightly clustered. Opendoor knows its sweet spot and generally sticks to it.

Our analysis shows an average appreciation of 5.5 percent from the price Opendoor buys houses for and what it ends up selling them for. Again, this figure is generally well-clustered, with the few loss-making outliers offset by a few big-profit outliers.

When we plug these figures into our model, we can build up a revenue estimate for the Phoenix market in 2016:

It’s possible that Opendoor books additional revenue from service fees when it buys a house, but the cash only hits its bank when a house is sold. Assuming another 400 houses in the Phoenix market that are active and will eventually sell, that’s another $7.8 million in booked revenue.

Cost and profitability

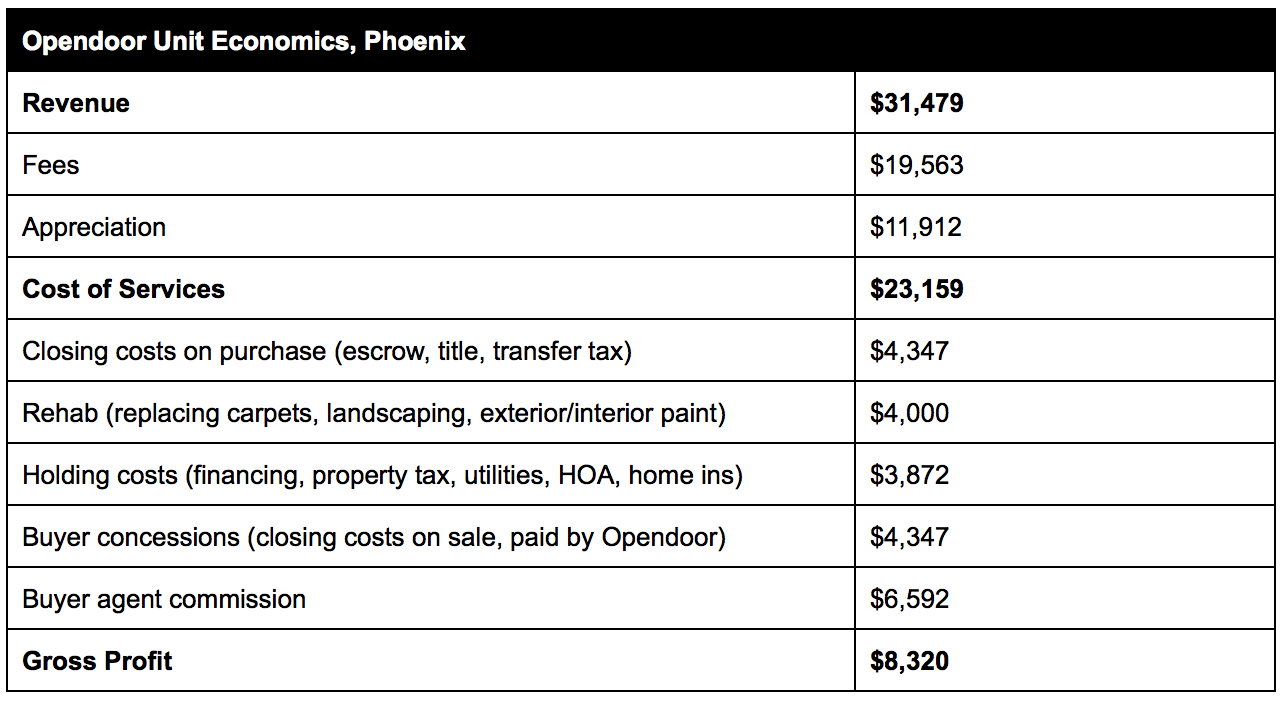

Opendoor’s seamless experience comes at a high price. By serving as an active middleman in the transaction, Opendoor effectively doubles transaction costs and incurs a wide variety of rehab and holding costs.

Below, we have done our best to estimate Opendoor’s gross profit per transaction in the Phoenix market. Again, we assume that on average Opendoor pays $217,370 for a home and charges a 9 percent fee, holds the home for 88 days, and sells it for 5.5 percent more than it paid:

Many costs are out of Opendoor’s control. For the foreseeable future, Opendoor will rely on the MLS to help it market and sell homes fast, making it tough to avoid paying the buyer agent commission. Phoenix is probably as good as it’s going to get in terms of closing costs, since it charges no transfer tax on real estate transactions.

Opendoor has more control over holding time and rehab expense. For every month Opendoor holds a home, it spends roughly $500 per $100,000 of home value. Flipping homes faster will lower the variable cost per transaction while freeing up dollars to deploy on the next purchase, reducing its effective cost of capital. By hiring in-house staff, buying supplies in bulk, and using data to identify high ROI improvements, Opendoor could shave precious basis points off the process of maximizing curb appeal.

There are two big takeaways here. First, given the costs associated with the middle-man model, it’s tough to imagine Opendoor being price competitive with agents. The best disruptors are both better and cheaper than incumbents, and we think cost has implications for Opendoor’s addressable market. Second, our analysis shows that on average, Opendoor’s fees barely cover its costs; appreciation on the sale is critical to profitability.

Fair value for homes?

Many people question whether Opendoor is really doing what it claims: offering a fair value for the houses it buys.

To recap: an analysis of 235 houses that Opendoor bought and eventually sold in the Phoenix market shows an average appreciation of 5.5 percent.

The analysis also shows an average of 20 days between the time Opendoor buys a house and then subsequently lists it back for sale. That gives its team three weeks to fix up and prepare a house for sale on the market. That’s a quick turnaround, and given that Opendoor generally borrows 90 percent of the purchase price and is servicing that debt, time is money!

Once a home is prepped and listed for sale again, what sort of premium does Opendoor list it at? The short answer is around $20,000.

There is a tight clustering right around the $20,000 mark, with an actual average of $21,570. But keep in the mind the final sales price is half of that, an average of $10,245 for our sample of 215 homes that sold.

At the end of the day, we believe it’s a fair assessment to say Opendoor offers generally fair offers for the houses they buy. It does not lowball sellers. But it does not seek the high returns that a typical home flipper would look for, only looking to recoup its investment in the property plus a small margin. (This conclusion was later validated in this extensive research study: Do iBuyers Like Opendoor and Zillow Make Fair Market Offers?)

Market opportunity

How big could Opendoor really get in the U.S. market? In order for Opendoor to reach $1 billion in annual revenues, we’d need to believe the following:

The key assumption is that each new market Opendoor enters can reach the same maturity level of Phoenix. There will be overs and unders in terms of market size, average house price, and closing costs. But for a quick, back-of-the-envelope estimate, we’re keeping things simple.

While we have no certainty of what future market traction will look like, we can look at the Dallas expansion (Opendoor’s second market) for early indications. It started listing properties in August and selling in September, giving us three month's worth of data to review.

The comparison above shows good traction -- just under half the volume of Phoenix in three months.

In other words, it’s not farfetched to imagine Opendoor reaching $1 billion in annual revenues. It sees its total addressable market as between 50 and 70 markets in the U.S., with plans to expand to 30 markets by 2018. Given the data we’ve seen, this is achievable. The major brakes on Opendoor’s ability to reach this scale are the availability of financing -- purchasing 30,000 houses a year would require a revolving credit line of approximately $1.5 billion, assuming its average hold period and purchase value stay the same -- and whether its automated valuation model will work well in markets that have less liquid and homogenous housing stock than Phoenix.

Risk

For investors and industry observers, the scariest part of the Opendoor model is market exposure of directly holding homes. To its credit, Opendoor clearly takes risk management seriously (it is hiring several capital markets and risk associates), and defends its robustness against market risk by making the following claims:

It can monitor price and market liquidity to detect a market correction early and adjust fees and home pricing, minimizing any loss.

As Opendoor gets bigger, it will have a more diverse portfolio of homes; all markets and asset types won’t collapse at the same time.

In a downturn, Opendoor doesn’t have to sell; for example, it can rent homes.

We’re most compelled by the first strategy. If Opendoor can predict a downturn before it’s widely known and shed old inventory fast with a preemptive discount, it can effectively employ a “stop-loss” mechanism that constrains the total downside.

We are less convinced by the second and third tactics. Diversification across U.S. geographies smooths risk in placid markets, but the most recent financial crisis suggests that American real estate markets are heavily correlated during the kind of market correction that would threaten Opendoor.

Finally, Opendoor’s ability to wait out a downturn by renting homes depends on the terms of its agreement with its debt issuer. We don’t know what that agreement looks like, but it isn’t likely to be as flexible as that of a hedge fund, for example, which often benefit from flexible investment mandates and “lock-up” periods where investors can’t get their capital back. In the last crisis, banks weren’t exactly known for their patience with capital calls.

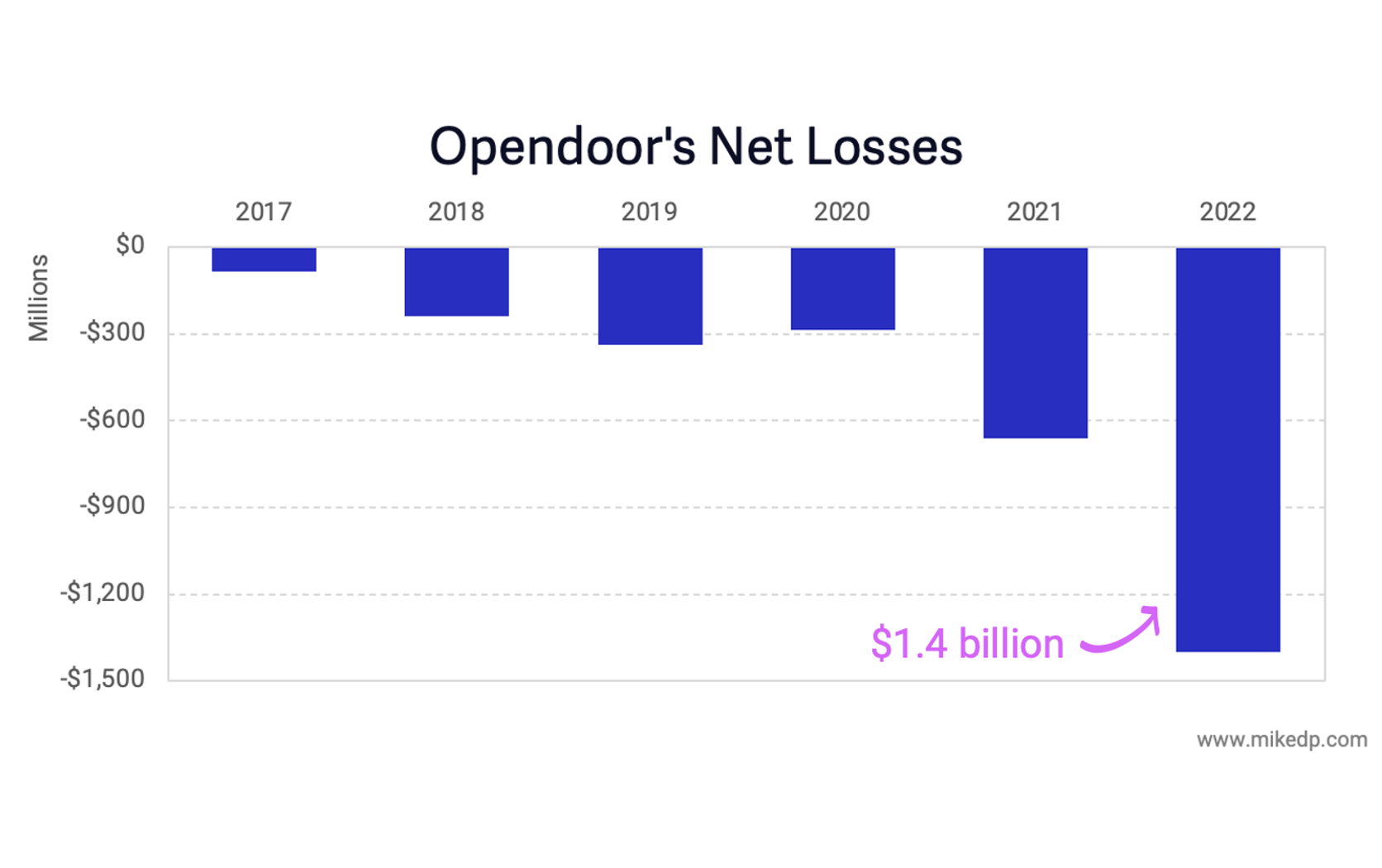

The indisputable fact is that Opendoor’s extraordinary opportunity also exposes it to deep and intrinsic risk. For the purpose of a venture investor with a five-year horizon, perhaps this doesn’t matter, but it raises questions about Opendoor’s ability to endure across economic cycles and exist as a durable franchise that permanently changes real estate. With such a thin margin, even a slight market shift could mean the difference between profit and loss.

Competitive advantage

Let’s assume that Opendoor’s model works well enough to attract the attention of potential copycats. What is the moat that will keep new entrants at bay? We’ve identified three sources of competitive advantage for Opendoor:

Proprietary automated valuation model (AVM)

Access to capital

Battle-tested and efficient flip process

Ultimately, we believe a major long-term risk to Opendoor is that the key elements of its seller customer experience -- a fast and well-priced offer -- are replicable. Lack of access to capital and an accurate AVM may keep smaller aspirants out, but won’t dissuade big asset managers from entering the fray; Blackstone has directly invested in residential real estate for years. If Opendoor continues to profitably flip homes, we don’t see a compelling reason why an institutional investor with deep pockets won’t enter the market by hiring data scientists (or licensing an AVM from Redfin or CoreLogic) and undercut Opendoor by offering to beat any offer by an extra grand.

If it comes down to the highest offer, Opendoor is still well positioned to win. Its trusted brand will provide a barrier against new entrants, a better automated valuation model will let it charge less for market risk, and its experience flipping homes will pay off in lower holding costs. But victory won’t be free: we predict that competitive pressure will drive Opendoor’s unit margin below where it sits today.

Concluding thoughts

The real value of Opendoor is that it’s forcing the industry forward. The current home selling process is filled with friction, and Opendoor should be applauded for taking a gutsy approach to solving many of these pain points in a single stroke.

The data and analysis above suggests that Opendoor has a sustainable business model. It is buying and selling hundreds of homes each month with upward traction. At scale, it is reasonable to see Opendoor generating over $1 billion in annual revenues and operating profitably. Traction and market potential like that cannot be ignored.

As the first mover and brand leader in this space, Opendoor is in a strong position, but we see two roadblocks that could prevent it from succeeding at scale. The first is proving out its risk management approach to the satisfaction of lenders who will need to issue a massive amount of debt to fund tens of thousands of home purchases. The second is figuring out how to differentiate from new entrants and avoid getting dragged into a race-to-the-bottom price war that would decimate its slim margins.

Whether or not Opendoor emerges as the eventual victor in this space -- is this model definitely the next step for residential real estate? The main barrier we see is cost. Opendoor could become a very successful business by serving even a small percentage of U.S. home sellers, but its addressable market will fall short of its true potential unless it can make its service both better and more affordable than the status quo.

A note on data: our analysis is based on MLS records, listings from Opendoor’s web site, the Maricopa City Assessor’s public property records, and public records sourced from Redfin. We used industry benchmarks to estimate the costs and fees associated with flipping homes in Phoenix. The data out is only as good as the data in, and the MLS system can be inaccurate. The analysis should be taken as such -- a review of available public records -- and not a verifiably complete picture. While absolute numbers may be off, we believe that directionally our analysis provides a very good look at the business.

Read every analysis I've posted on Opendoor, Zillow Offers, and the iBuyer business model.

The 2020 iBuyer Report

The iBuyer Report is a 150+ slide, evidence-based look at the world of instant home buyers. Unmatched in its breadth and depth, it explores behind-the-scenes, national data and presents an unbiased strategic analysis of the sector, the players, and the implications for the industry.